An Explanation Of The Minimax Algorithm

Intro

I’ve been working on a javascript based tic-tac-toe game, and I was tasked with making an unbeatable AI utilizing the mini-max algorithm. In the past I’ve tried to create a “hard coded” unbeatable AI that accounted for every possible scenario. In reality the code was incredibly complex and admittedly…not pretty. In this post I plan on taking my Javascript mini-max code and walking through how the mini-max algorithm works.

Since I will only be focusing on my mini-max function I will not be including all my code here. If you would like to see the rest of my code please visit my repo.

My Mini-Max Function

ComputerLogic.prototype.minimax = function(gameBoard, depth, marker) {

var availableSpots = ComputerLogic.prototype.getAvailableSpots(gameBoard);

if (self.winConditions.isGameOver(gameBoard)) {

return ComputerLogic.prototype.getScore(depth, gameBoard, marker);

}

var moves = [];

for (var i = 0; i < availableSpots.length; i++) {

var moveValues = {};

moveValues.spot = availableSpots[i];

var gameBoardCopy = gameBoard.slice();

gameBoardCopy[availableSpots[i]] = marker;

var result = ComputerLogic.prototype.minimax(gameBoardCopy, depth + 1, marker === "O" ? "X":"O");

moveValues.score = result.score;

moves.push(moveValues);

}

var bestMove;

if(marker === "O") {

var max = -1000;

for(var i = 0; i < moves.length; i++) {

if (moves[i].score > max) {

max = moves[i].score;

bestMove = i;

}

}

} else {

var min = 1000;

for(var i = 0; i < moves.length; i++) {

if (moves[i].score < min) {

min = moves[i].score;

bestMove = i;

}

}

}

return moves[bestMove];

}

The Break Down

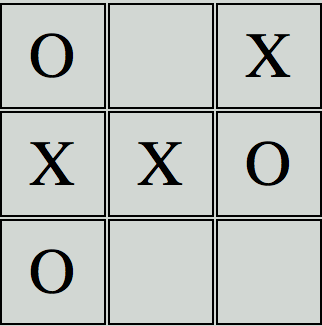

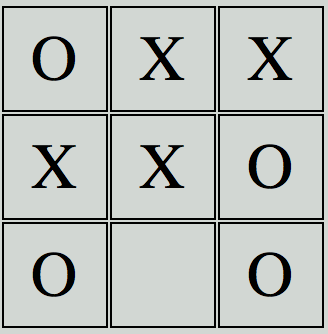

I want to attempt to explain what mini-max is trying to accomplish in order to provide some context. The goal of the algorithm is to cycle through a game board and essentially play every possible game and score until the ending game conditions. The reason why they call it “mini-max” is because the computer is trying to maximize its outcome and minimize the opponents outcome. By “outcomes” I’m referring to scores given to end of game states: a win, a loss, or a tie. Every game is scored where the computer scores it’s wins positively (with a positive number) and scores it’s opponent’s wins negatively (with a negative number). The reason why it does this is so that it can choose a game path with a positive outcome which could lead to a win or tie. To provide a quick example let’s take a look at the game below, which is nearing it’s end:

Here, it is our Human Players turn, X. Given that X would like to still be able to win he has two options he can choose, which are the top middle and the bottom middle positions. Let’s say X chooses the top middle position.

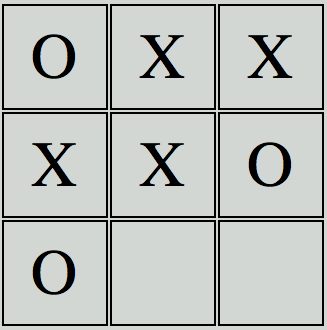

Here, our computer, O, has two options. It can either block a potential X win by choosing the bottom middle position or choose the bottom right position, which effectively does nothing for O. Now, if mini-max was used during this game it would have two scenarios to play through. in this case it would give a score of “0” for a tie with the human player and a arbitrary negative score, I used “-10” in my game, for a human player win. Remember that the computer wants to minimize the potential player win outcome, which would be represented by a negative score. So, mini-max would play through both these scenarios and score. Here is the first scenario:

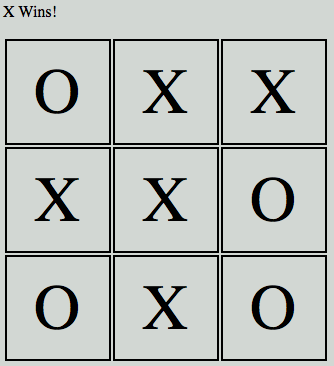

Computer Moves

Human Player Moves

Final Score: 0

Now to be clear mini-max will make moves for both the computer and the human player to determine the best outcome for the computers sake. For this particular scenario, since an end of game state has been reached, tie game, it will score this situation as a 0 since it is a tie.

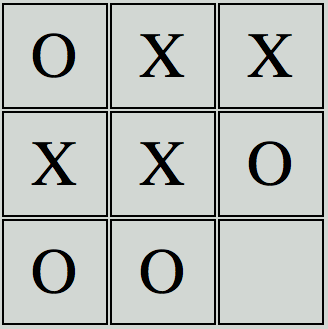

How about if it went through the second scenario:

Computer Moves

Human Player Moves

Final Score: -10

Now this ending game state yields a -10 score. Not good for the computer! The computer wants a positive score, which would symbolize a computer win. Now there is no +10 score, which would symbolize a computer win in this scenario, but the highest score possible in this case is a 0 since 0 > -10. Thus, mini-max will place its symbol in the bottom center position to not only block the human player, but to get to the tie as opposed to the X win.

This is obviously a small piece of what mini-max does. If the scenario was different and O had an opportunity to win it would choose that route with a +10 score, which is equal and opposite of the X win score. As you could probably already imagine it would be incredibly difficult/time consuming to walk through an entire game. So, instead lets walk through the code in little chunks and discuss what the algorithm is doing.

Obtaining Available Spots on the Board

On our first stop, let’s take a look at the first line of code. The goal of my first line of code is to take my game board, which is an array, and find any available spaces on the board. All those spots are stored in an array called “availableSpots.”

var availableSpots = ComputerLogic.prototype.getAvailableSpots(gameBoard);

In our earlier example you might be able to see why a list of available spots might be important. The AI has to have the ability to evaluate every move that is available to the AI, thus the AI needs to know which spots are available for marker, “O”, placement.

Scoring an End of Game State

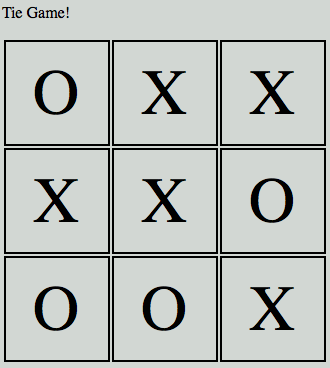

As we saw in our example, we have to have the ability to score the end of every game so we know the potential result of a particular move. Now if you think of game play as a tree of many options you might envision an image like the following:

1

In this image we are nearing the end of the game. Notice that each game is labeled with a letter, A, B, C, etc. I will use these letters as a guide down the tree for multiple examples.

So, let’s look at the code:

if (self.winConditions.isGameOver(gameBoard)) {

return ComputerLogic.prototype.getScore(depth, gameBoard, marker);

}

Not much can be determined from this piece of code alone, but let’s look at the conditional in the “if” statement first. What “self.winCOnditions.isGameOver(gameBoard)” is doing is it is looking for end of game states. So, if the game ends in a win or a tie it returns true, thus moving down to the scoring process. Since, my scoring is not visible in this algorithm, I’ll post it below:

ComputerLogic.prototype.getScore = function(depth, gameBoard, marker) {

marker = marker === "O" ? "X":"O";

if (marker == "O" && self.winConditions.isWinner(gameBoard)) {

return {score: 10 - depth};

} else if (marker == "X" && self.winConditions.isWinner(gameBoard)) {

return {score: depth - 10};

} else if (self.winConditions.isTie(gameBoard)) {

return {score: 0};

}

}

For continued simplicity let’s ignore the “depth” variable for now as it is more of a means to optimize/manipulate the way your AI will choose a space. If you are interested in making an AI with a variety of skill levels, take an opportunity to research how “depth” can be utilized.

The first line is used as a means for me to switch the marker of the player.

marker = marker === "O" ? "X":"O";

I had to switch the marker because the player that has made the last move is the opposite marker. Confusing? I’ll come back to this in a bit, but know that the player that made the last move and won is opposite of the marker that is entering the function. Now we have an if…else if…else if statement. Each piece of this statements checks to see if someone has won or if there is a tie. For example the code below is saying “If the marker is equal to O and there is a winner then return an object with a score of 10 - depth.” So, as I mentioned before, let’s ignore depth and treat this as a score of just “10.” As we move down we see “if X wins apply a score of depth - 10,” which we will represent as “-10.” The last part of the statement searches for a tie game and returns a score of “0.”

Cool, now that we know that O wins are scores as +10, X wins are scored as -10, and ties are scored as 0, we can continue to dive deeper.

Big, Bad, Recursion!

This is usually the piece of mini-max that most people will trip up on. Are goal is to allow the AI to play every possible game and return a score for the end of game states for each branch of the game.

Let’s take a look at our game tree. At the top of the tree we have a game board with 3 available spots and it is X’s turn. I know that we have been talking about X = player and O = computer, but let’s switch that up for this example (Sorry, but this image was too good to pass up on!). So, lets walk through the code:

var moves = [];

for (var i = 0; i < availableSpots.length; i++) {

var moveValues = {};

moveValues.spot = availableSpots[i];

var gameBoardCopy = gameBoard.slice();

gameBoardCopy[availableSpots[i]] = marker;

var result = ComputerLogic.prototype.minimax(gameBoardCopy, depth + 1, marker === "O" ? "X":"O");

moveValues.score = result.score;

moves.push(moveValues);

}

The first line of code I have created an array called moves that stores score objects as well as the position objects that lead to that particular score. Then we begin a for loop. This loop is incredibly important as it allows the AI to go through the availableSpots array and places a marker on each spot. So, the first spot is chosen and a marker is placed on a copy of the current game board.

gameBoardCopy[availableSpots[i]] = marker;

And now the magic happens! The next line of code is hands down one of the most important parts of this whole process. This part calls back the mini-max method and goes through the whole method again, while keeping note of the previous state in memory. What does that mean? Well, lets say the computer, who is now X, if you recall me mentioning that earlier, chooses spot number 8 represented by diagram “C” in the tree. That “C” state of the board will wait for all of the moves below to be played and it ultimately waits until an end state is reached and returns a score. While it is “waiting,” all those moves are using the recursion to play out each scenario below diagram C. It is taking turns for both the human and the computer player. Notice on the left side of the diagram it says X’s turn, O’s turn and continues all the way down. So if we go down the tree for Diagram C there are two potential end states, I, which is a win for X (score: +10) and J, which is a tie (score: 0). Both of these scores will be returned and stored in my moves array. You may need to review this process a couple times, but just think of the recursion going and going and going, until it reaches an end state and comes back up, where the score is stored and then moves on in the code.

Return the Best Move

The code after the recursion is just a means to loop through all of the scores scored in the array and return it. Now, it is kinda weird to think about, but the board states under diagram C where we started have already gone through this code. Now it is Diagram C’s turn to organize the scores that were returned to it.

var bestMove;

if(marker === "O") {

var max = -1000;

for(var i = 0; i < moves.length; i++) {

if (moves[i].score > max) {

max = moves[i].score;

bestMove = i;

}

}

} else {

var min = 1000;

for(var i = 0; i < moves.length; i++) {

if (moves[i].score < min) {

min = moves[i].score;

bestMove = i;

}

}

}

Now notice that there are two ways to organize scores. There is a way to organize “O” scores and “X” scores. Now, I represented my computer as “O” so notice that if marker === “O”, I am looking for the highest positive score and for the human player I am looking for the most negative score.

Once my scores are organized the best move is returned with the following:

return moves[bestMove];

In the computers case, the best move would yield the largest positive score so that position that lead to the positive score is what the computer will use to make a move.

Conclusion

I have to preface all this with mini-max is not easy to learn. If you don’t get it now, you eventually will and when you do it will become very clear as to what is going on. I worry that I may have glanced over certain aspects that I may have thought were obvious, but they are only obvious to me now that I understand the algorithm. If you have any questions or need help, please feel free to reach out and I would be happy to help!

1 Definitions. (2003). Gamesman. Retrieved from https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~ddgarcia/teaching/CS3Gamesman/assignment/definitions.html